Australian System of National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods

This publication outlines the major concepts, definitions, data sources and methods used to prepare the National Accounts estimates

Preface

The national accounts explain how the Australian economy operates, and how it evolves over time, by measuring, classifying, and aggregating these transactions. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the highest profile estimate, but the Australian System of National Accounts (ASNA) cover a range of other economic measures. These include a full set of flow accounts for each sector of the economy (income, capital and financial), input-output (I-O) tables, supply-use (S-U) tables, satellite accounts, state-based estimates, balance sheets, reconciliation accounts, and productivity estimates.

This publication is a guide to the Australian System of National Accounts. It outlines the major concepts and definitions, describes the data sources and methods used to prepare the estimates, and discusses the accuracy and reliability of the national accounts.

It is designed for both intensive users, such as economic and financial analysts, as well as less intensive users looking to gain a better understanding of national accounts, or the Australian economy in general.

This is the seventh edition of Australian System of National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods. The chapters released in this edition have been updated to reflect changes made to the sources and methods used to compile the Australian System of National Accounts undertaken since the sixth edition.

This is consistent with the following ABS publications, inclusive of the most recent releases:

- Australian System of National Accounts (annual publication)

- Australian National Accounts: State Accounts (annual publication)

- Australian National Accounts: Tourism Satellite Account (annual publication)

- Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product (quarterly publication)

- Australian National Accounts: Finance and Wealth (quarterly publication)

The first edition of the Australian System of National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods, in its current format, was published in July 2012. This was timed to reflect implementation of the 2008 System of National Accounts (2008 SNA), the Sixth Edition of the IMF’s Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual (BPM6) and the 2006 Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC06).

The second edition was published in September 2012, and included the chapter on the concepts, sources and methods that underpin the Australian input-output tables.

The third edition was published in December 2012, and included five additional chapters covering productivity and analytical measures; state accounts; satellite and environmental-economic accounts; and the quality of the national accounts.

The fourth (December 2013), fifth (January 2015), sixth (March 2015) and seventh (July 2021) editions reflected changes to the sources and methods used to compile the Australian System of National Accounts. None of these editions included new chapters.

The seventh edition was the last to be released in a pdf format before the ABS launched a web-based version of this publication in 2022.

Katherine Keenan

Program Manager, Production, Income and Expenditure

Updates

In 2024, the ABS embarked on a program to update the web-based version of Australian System of National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods on an ongoing basis. This will ensure users have access to the most up-to-date concepts, data sources and methodologies used to compile the National Accounts.

Updates are listed below by chronological order starting with March 2024. The specific details of content changes are provided under the relevant section along with previous content for comparison.

March 2024

October 2024

Data Download - Printable version

To view the original version of the seventh edition as a pdf file click here.

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 This chapter describes the nature, purpose and history of the Australian System of National Accounts as well as key improvements since the previous update in 2015. The ASNA is based on the international standard, the System of National Accounts, 2008. The 2008 SNA ensures consistency with related manuals, such as the International Monetary Fund Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, Sixth Edition, which was updated simultaneously with the 2008 SNA, as well as Australian Government Finance Statistics, Concepts, Sources and Methods 2015 (AGFS15). Coinciding with the implementation of the revised international standards, the ASNA currently adopts the 2006 Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification.

1.2 Although balance of payments and government finance statistics are an integral part of the Australian National Accounts, a description of concepts and data sources used for these statistics is included only for those aggregates that appear in the National Accounts. A detailed discussion of the key improvements introduced into the ASNA as a result of 2008 SNA implementation can also be found in Information Paper: Implementation of new international statistical standards in ABS National and International Accounts, (September 2009). For a more detailed description of balance of payments statistics, see Balance of Payments and International Investment Positions, Australia: Concepts, Sources and Methods and for Government Finance Statistics, see AGFS15.

Nature, purpose and history of National Accounts

Nature and purpose of National Accounts

1.3 National Accounts provide a systematic statistical framework for summarising and analysing economic events, the wealth of an economy, and its components. Historically, the principal economic events recorded in the National Accounts have been production, consumption, and accumulation of wealth. National Accounts have also recorded the income generated by production, the distribution of income among the factors of production and the use of the income, either for consumption or acquisition of assets. The modern accounts additionally record the value of the economy's stock of assets and liabilities, and record the events, unrelated to production and consumption, that bring about changes in the value of the wealth stock. Such events can include revaluations, write-offs, growth and depletion of natural assets, catastrophes, and transfers of natural assets to economic activity.

1.4 The national accounting framework has always consisted of a set of accounts that are balanced using the principles of double entry accounting. However, the accounts are now fully integrated in that there is a balance between the value of assets and liabilities at the beginning of an accounting period, the transactions and other economic events that occur during the accounting period, and the closing values of assets and liabilities. Accounts for the economy as a whole are supported by accounts for the various sectors of the economy, such as those relating to the government, households and corporate entities. The framework also embraces other, more detailed, accounts such as financial accounts and I-O tables, and provides for additional analyses through social accounting matrices and satellite accounts designed to reflect specific aspects of economic activity such as tourism, health and the environment. By applying suitable price measures, the National Accounts can be presented in volume terms as well as in current prices. The time series of the National Accounts can also be adjusted to remove seasonal distortions and to disclose trends.

1.5 National accounting information can serve many different purposes. In general terms, the main purpose of the National Accounts is to provide information that is useful in economic analysis and formulation of macroeconomic policy. The economic performance and behaviour of an economy as a whole can be monitored using information recorded in the National Accounts. National Accounts data can be used to identify causal relationships between macroeconomic variables and can be incorporated in economic models that are used to test hypotheses and make forecasts about future economic conditions. Using National Accounts data, analysts can gauge the impact of government policies on sectors of the economy, and the impact of external factors such as changes in the international economy. Economic targets can be formulated in terms of major national accounting variables, which can also be used as benchmarks for other economic performance measures, such as tax revenue as a proportion of gross domestic product or the contribution of government to national saving. Provided that the National Accounts are compiled according to international standards, they can be used to compare the performance of the economies of different nations.

1.6 However, the full range of information available from a comprehensive national accounting system can serve purposes well beyond immediate concerns of macroeconomic analysts. For example, National Accounts information can be used to analyse income and wealth distribution, financial and other markets, resource allocation, the incidence of taxes and welfare payments, environmental issues, productivity, industry performance, and so on. In fact, the range of analytical purposes that can be served by a complete system of National Accounts has no well-defined limits, and the body of National Accounts data can be seen as a multi-purpose data base that can be used with a high degree of flexibility.

1.7 Surveys and other statistical systems that employ the concepts in the national accounting framework will produce information that is consistent with the National Accounts and with other statistics that are based on the National Accounts framework.

Brief history of National Accounts

1.8 The idea of estimating national income can be traced back to the seventeenth century. Interest in raising revenue and in assessing England's war potential led to attempts by Sir William Petty in 1665 and Gregory King in 1688 to estimate the national income as either the sum of factor incomes or the sum of expenditures. A little later, Boisguillebert and Vauban used a similar approach in estimating France's national income.

1.9 The eighteenth century French economists called the Physiocrats took a step backwards when they restricted the concept of national income by arguing that only agriculture and the extractive industries were productive. However, Quesnay, one of the Physiocrats, set out the interrelationships between the various activities in the economy in his tableau economique, published in 1758, which was the forerunner of the twentieth century work on I-O statistics.

1.10 In his book, the An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith rejected the Physiocrats' view of the pre-eminent position of agriculture, by recognising manufacturing as another productive activity. However, Smith and the early classical school of economists that he founded did not recognise the rendering of services as productive activity. Karl Marx was also of this view, and the notion persisted in the material product system of National Accounts that was used, until recently, by the centrally planned economies.¹

1.11 Some English economists, in particular Ricardo and Marshall, further refined the concept of production and in the 1920s the welfare economists led by Pigou undertook the first effective measurement of national income.

1.12 The Great Depression of the 1930s, and the attempts by Keynes and others to explain what was happening to the world economy, led economists away from their preoccupation with national income as a single measure of economic welfare. Instead, they attempted to use the new Keynesian General Theory to develop a statistical model of the workings of the economy that could be used by government to develop prescriptions for a high and stable level of economic activity. By the end of the 1930s, the elements of a national accounting system were in place in several countries. The models of Ragnar Frisch and Jan Tinbergen stand out in this period as path-breaking achievements.

1.13 The economic modelling task was given further impetus in the 1940s; first, by the need to efficiently run war-time economies; second, by the publication in 1941 of Wassily Leontief's classic I-O study The Structure of the American Economy; third, by the post-war acceptance by governments of full responsibility for national and international economic management; and last, by the League of Nations publication of an important report about social accounting. By the end of the decade, integrated statistical reporting systems and formal national accounting structures were in place in Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, the Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands and France.

1.14 The need of international organisations for comparable data about the economies of member countries was one important factor that prompted development of international standards for national accounting in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The Organisation for European Economic Co-operation sponsored the work of Richard Stone's National Accounts Research Unit at Cambridge University, from which emerged the now-familiar summary accounts of the nation.² Then the United Nations Statistical Office convened its first expert group on the subject. It was also headed by Stone and, in 1953, produced the publication, A System of National Accounts and Supporting Tables (SNA)³, which described the first version of the system that has become the accepted world-wide standard for producing National Accounts.

1.15 There were several other important developments in national accounting in the 1950s. M.A. Copeland and his colleagues in the United States Federal Reserve System prepared the first flow-of-funds tables, which analysed transactions in financial markets. A few countries increased the frequency of National Accounts information by producing quarterly estimates of national income and expenditure (so that their governments could better monitor the business cycle) and also produced information classified by industry and institutional sector (to identify growth industries, poorly performing institutional sectors etc.).

1.16 National accounting's modern era could be said to have started in 1968. In that year, the United Nations Statistical Office published a fully revised version of the SNA, which drew together all the various threads of economic accounting: estimates of national income and expenditure (including estimates at constant prices); I-O production analysis; flow-of-funds financial analysis; and balance sheets of national wealth.⁴ In 1977 the United Nations Statistical Office published detailed international guidelines on the compilation of balance sheet and reconciliation accounts within the SNA framework.⁵

1.17 Since 1968, changes in the structure and nature of economies, the increasing sophistication and growth of financial markets and instruments, emphasis on the interaction of the economy with the environment and other considerations pointed to a need to update the SNA. The task of updating and revising the SNA was coordinated from the mid-1980s by the Inter-secretariat Working Group on National Accounts, working with the assistance of international organisations and experts from national statistical offices around the world. The Working Group consisted of the Commission of the European Communities (Eurostat), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the United Nations (UN) and the World Bank. The resulting 1993 SNA was released under the auspices of those five organisations.⁶

1.18 The 1993 SNA aimed to clarify and simplify the 1968 System, while updating the System to reflect new circumstances. The 1993 SNA fully integrated national income, expenditure and product accounts, I-O tables, financial flow accounts and national balance sheets to enable the examination of production relationships and their interaction with countries' net worth and financial positions. 1993 SNA also introduced the concept of satellite accounts to extend the analytical capacity of National Accounts in areas such as tourism, health and the environment. It was one of a quartet of 'harmonised' international statistical standards that included the standards set out in the IMF publications, Balance of Payments Manual 1993 (fifth edition) (BPM5), Manual of Monetary and Financial Statistics (MMFS), and A Manual of Government Finance Statistics (second edition) (GFS). In this context, 'harmonisation' means that the standards employ common concepts and definitions so that valid comparisons can be made of statistics produced from each of the four systems. Complete alignment of the standards was neither feasible nor necessary, because each system serves different purposes. Each system therefore had a proportion of unique concepts and definitions.

1.19 The 2008 SNA was commissioned by the United Nations Statistical Commission to bring the national accounting framework as outlined in the 1993 SNA into line with the needs of data users. It was considered that the economic environment in many countries has evolved significantly since the early 1990s and, in addition, methodological research had resulted in improved methods of measuring some of the more difficult components of the accounts. The 2008 SNA does not recommend fundamental or comprehensive changes. Further consistency with related manuals, such as those on the balance of payments (which was updated simultaneously with the 2008 SNA), on government finance statistics and on monetary and financial statistics, was an important consideration. Therefore, there is more harmonisation between the 2008 SNA and related manuals. The key changes fell into five main groups: assets; the financial sector; globalisation and related issues; the general government (GG) and public sectors; and the informal sector. Australia's policy is to apply each of the standards to the highest feasible degree, a high level of harmonisation will be found between the Australian National Accounts and Australia's balance of payments, government finance, and monetary and finance statistics.

Endnotes

National Accounts in Australia

1.20 Australia pioneered work on national wealth in 1890 when Coghlan (the New South Wales Government Statistician) prepared rudimentary balance sheets for New South Wales. However, it was not until almost sixty years later, at the Conference on Research in Income and Wealth in 1948, that national balance sheets again received serious international attention.

1.21 The first official estimates of national income for Australia (based on estimates prepared by Clark and Crawford) were published in 1938 in The Australian Balance of Payments, 1928-29 to 1937-38, although unofficial estimates by several economists had been published in the 1920s and 1930s.⁷ In 1945, the first official set of National Accounts was prepared by the then Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics (CBCS) and published in the Commonwealth Budget Paper Estimates of National Income and Public Authority Income and Expenditure.

1.22 The 1960s and early 1970s were times of significant development for Australian national accounting. The first official quarterly estimates of national income and expenditure were published in December 1960.⁸ In 1963 the CBCS published the first Australian National Accounts: National Income and Expenditure (ANA) bulletin, which included the first annual constant price estimates for Australia.⁹ Experimental I-O estimates were published in 1964.¹⁰ The CBCS began to seasonally adjust its quarterly estimates of national income and expenditure in 1967. Estimates of gross product by industry at constant prices were published for the first time in 1969.¹¹ In 1971, the CBCS first published seasonally adjusted, constant price quarterly estimates of national income and expenditure, which later proved to be among the most used of all national accounting estimates. The CBCS published estimates of national income and expenditure based on the revised SNA (1968 version) in 1973, and also published the first official I-O statistics in the same year.¹²

1.23 In the 1980s, the former CBCS, now called the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), again made significant progress in national accounting. The first full edition of Australian National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods was published in 1981 at about the same time as the first experimental estimates of capital stock.¹³ The ABS conducted a study into the accuracy and reliability of the quarterly estimates of national income and expenditure and published the results in 1982.¹⁴ Experimental State accounts¹⁵ were published in 1984, followed by the first official estimates in 1987.¹⁶ They are now published annually in Australian National Accounts: State Accounts. In 1985, the ABS published an assessment of the effects of rebasing constant price estimates from a 1979-80 base to a 1984-85 base.¹⁷ In 1986, the second set of experimental estimates of capital stock was published¹⁸ followed in 1987 by the first official estimates of capital stock.¹⁹ The first quarterly estimates of constant price gross product by industry were released in 1988.²⁰ These estimates were subsequently incorporated into the quarterly publication, Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product.

1.24 Further significant developments in national accounting and associated statistics occurred during the 1990s. In 1990, the first estimates of multifactor productivity were published.²¹ In 1990, the ABS also published developmental flow of funds accounts, showing the changes in financial assets and liabilities arising from the financing of productive activity in the economy.²² Flow of funds estimates are now published on a quarterly basis, along with estimates of stocks of financial assets and liabilities at the end of each quarter. An Information Paper describing the impact of rebasing constant price estimates from a 1984-85 base to a 1989-90 base was published in 1993.²³ Experimental estimates of national balance sheets for Australia were first released in 1995, followed by the publication of regular annual national and sector balance sheet estimates in 1997.²⁴ Australian National Accounts: Supply Use Tables commencing 1994-95 were first introduced (but not published) into the annual National Accounts in 1998, in conjunction with the implementation of 1993 SNA, as an integral part of the annual compilation of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). They ensure GDP is balanced for all three approaches (production, expenditure and income) and provide the annual benchmarks from which the quarterly estimates are compiled.

1.25 The 1993 SNA was formally introduced into the National Accounts in the September quarter 1998 issue of Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, which was released in December 1998. Prior information on the nature and impact of implementation of the revised standards and methods was provided in a series of discussion and information papers as follows:

- Discussion paper: Introduction of Revised International Statistical Standards in ABS, December, 1994.

- Information Paper: Implementation of Revised International Standards in the Australian National Accounts, September, 1997.

- Information Paper: Australian National Accounts, Introduction of Chain Volume Measures and Price Indexes, March, 1998.

1.26 Preliminary data on a 1993 SNA basis were made available in re-releases of the following publications:

- Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, June quarter, 1998 re-released in November 1998 in Information Paper: Upgraded Australian National Accounts.

- Australian National Accounts: Finance and Wealth, June quarter, 1998 re-released in December 1998 in Information Paper: Upgraded Australian National Accounts.

1.27 The first annual national accounts publication on a 1993 SNA basis was Australian System of National Accounts, 1997-98, released in April 1999. This publication provided comprehensive national and sectoral accounts, including balance sheets, as well as estimates of capital stock and multifactor productivity. A significantly updated edition of Australian National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods was published in 2000. It outlined the implementation of the 1993 SNA in the national accounts statistics of Australia.

1.28 There were major changes to the Australian tax system from 1 July 2000 with the introduction of The New Tax System (TNTS). A major feature of the new arrangements was the introduction of a goods and services tax (GST), which affected the prices of a broad range of goods and services in the economy. The GST replaced wholesale sales taxes (WST) and a number of other taxes on production and imports, although not all of these taxes were abolished from 1 July 2000. The introduction of the GST was accompanied by reductions in personal income tax rates and increases in social security payments. There were also changes to company tax arrangements. The information paper, ABS Statistics and The New Tax System, and the feature article in the March quarter 2000 issue of Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, provide more detail on the impact of this change. The TNTS was introduced into the National Accounts in the September quarter 2000 issue of Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product and 2000-01 issue of the Australian System of National Accounts.

1.29 The first Australian National Accounts: Tourism Satellite Account, 1997-98 was published in 2000 on a pre-GST basis and post-GST from 2002 annually. There have been other satellite accounts published occasionally, namely the Australian National Accounts: Non-Profit Institutions Satellite Account in 2002 and 2009, and the Australian National Accounts: Information and Communication Technology Satellite Account in 2006.

1.30 A significant development in state accounts occurred in 2007 with the estimation of Gross State Product using the production approach (GSP(P)). Consequently, the headline measure of GSP was the average of the existing GSP estimated using the income/expenditure approach and GSP(P). The first estimates were released in Australian National Accounts State Accounts in 2006-07. The information paper, Gross State Product using the Production Approach GSP(P) outlined the methods and sources for estimating GSP(P).

1.31 In February 2012, the System of Environmental and Economic Accounting (SEEA) was elevated as an international statistical standard. Additional parts to the SEEA, namely applications and ecosystems, are still in development. This development process occurred over many years and the ABS was, and will continue to be, at the forefront of the international efforts. Crucially, the SEEA is fully integrated with SNA concepts and therefore provides harmonised information across the environment and economic domains. Where necessary, environmental accounting can extend the asset and production boundaries of the SNA framework to better encapsulate the environment and its resources. The ABS releases a range of annual accounts including Water Account, Australia and Energy Account, Australia and Waste Account, Australia, Experimental Estimates. Land accounts for selected States and regions of Australia are also available, and progress has been made developing environmental expenditure accounts (see discussion paper).

1.32 The 2008 SNA was formally introduced into the National Accounts in the September quarter 2009 issue of Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product and the annual release of Australian System of National Accounts, 2008-09, which were released in December 2009. Prior information on the nature and impact of implementation of the revised standards and methods was provided in the following information papers:

- Information Paper: Introduction of Revised International Standards in ABS Economic Statistics in 2009, September, 2007

- Information Paper: Implementation of New International Standards in ABS National and International Accounts, October, 2009

1.33 The standards set out in the 2008 SNA (as well as 1993 SNA) are designed to be applied with a degree of flexibility, and Australia's implementation of the standards reflect local conditions and requirements. Furthermore, decisions are made in isolated instances to depart from the standards because of strong user preference for an alternative view and such departures are noted at appropriate points throughout this manual. The departures are relatively minor and, consequently, they do not affect the comparability of National Accounts information reported by the ABS to international organisations such as the UN and the OECD to a significant extent. A list of the main departures from 2008 SNA is provided in Appendix 2.

Endnotes

Purpose of concepts, sources and methods

1.34 The main purpose of this manual is to provide users with an in-depth understanding of the National Accounts statistics as an aid to more effective use and interpretation of the statistics. A detailed understanding of the underlying statistical standards and concepts, and of the methods used to compile the statistics, should enable users to make better judgements about the economic significance, quality and accuracy of the statistics. To achieve this aim, this manual provides an updated account of the concepts, sources and methods used to compile the Australian National Accounts statistics. A number of appendices are also included to provide additional information on particular aspects of national accounting, such as the classifications underlying the accounts.

1.35 Wide spectrums of audiences require information about National Accounts concepts, sources and methods. These range from users with broad, general needs for information about the main aggregates to those with highly specialised needs relating to particular data items. The main categories of users, and their likely needs, are set out below:

- students at upper high school level or undergraduate level at university – the need is for a broad understanding of the conceptual framework, how the numbers are put together, and the main outputs (publication tables, written and graphic analysis, and explanatory notes) to gain an appreciation of the current performance of the Australian economy;

- financial journalists – the need is for a broad understanding of the conceptual framework, how the numbers are put together, and the main outputs, to support media comment on the current performance of the Australian economy. These users may need to delve deeper into particular aspects;

- teachers/teaching academics – a broad understanding of the conceptual framework, how the numbers are put together, and the main outputs, to support teaching about Australia’s economy. These users may also need to delve deeper into particular aspects;

- financial sector economists, economists working for interest groups, national and international investors, public sector economists in other countries, and international credit rating agencies – a reasonably detailed understanding of the conceptual framework, the sources and how the numbers are put together, to support their interpretation of the statistics and advice to their organisations and clients;

- international agencies such as the IMF, the OECD, the World Bank and the United Nations Statistics Division – generally these agencies require a reasonably detailed understanding of all aspects of the statistics. Their uses encompass monitoring the extent of country adherence to international standards and practices, the compilation of country groupings and world economic statistics, and modelling work to support the preparation of country reports;

- academic researchers – a reasonably detailed understanding of the conceptual framework, the sources, and how the numbers are put together, with more detail on particular accounts/items to support research and modelling;

- National Accounts compilers in other countries – a reasonably detailed understanding of Australian sources and methods, with more detail on particular accounts/items, to compare with their own practices; and

- the Commonwealth Treasury, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), the Productivity Commission and other public sector economists – a reasonably detailed understanding of Australian sources and methods to support their interpretation of the numbers and forecasting of national accounting aggregates.

1.36 For students and others who need only a broad understanding of the National Accounts statistics, the ABS publication, Measuring Australia’s Economy provides a brief overview of the concepts, structure and classifications of these and the other major economic statistics published by the ABS. The present concepts, sources and methods document should prove a useful extension, but for the most part it may be too detailed for this audience.

1.37 The present document is aimed mainly at the user of National Accounts statistics who is interested in the more detailed aspects. However, it is not a complete description of the ABS National Accounts methodology. That task would require a much larger publication. This publication aims to provide a substantial guide to what the ABS does to compile National Accounts.

The Australian System of National Accounts

Scope of the Australian System of National Accounts

1.38 The ASNA forms a body of statistics that incorporates a wide range of information about the Australian economy and its components. In addition to the long-standing statistics of national income, expenditure and product, the accounts include the financial accounts, I-O tables, balance sheet statistics (including capital stock statistics), multifactor productivity statistics, state accounts, and satellite accounts. The ultimate scope of the ASNA encompasses the full range of statistics that the 2008 SNA recommends for a complete national accounting system. However, like most other countries, Australia does not yet compile the full range of information recommended in the 2008 SNA. The areas where the ABS is yet to implement the 2008 SNA recommendations are identified at relevant points throughout this manual and are summarised in Appendix 2, Differences between ASNA and 2008 SNA.

1.39 The current scope of the ASNA is best described by the list of statistical bulletins that comprise the ASNA data. These are as follows:

- Australian System of National Accounts (ASNA) – annual;

- Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product (NIEP) – quarterly;

- Australian National Accounts: Input-Output Tables – annual;

- Australian National Accounts: Supply Use Tables – annual;

- Australian National Accounts: State Accounts – annual;

- Australian National Accounts: Finance and Wealth – quarterly;

- Estimates of Industry Multifactor Productivity – annual;

- Estimates of Industry Level KLEMS Multifactor Productivity – annual;

- Australian National Accounts: Tourism Satellite Accounts – annual;

- Australian National Accounts: Non-Profit Institutions Satellite Accounts – irregular; and

- Australian National Accounts: Information and Communication Technology Satellite Accounts – irregular.

1.40 The data on capital stock and balance sheet that were previously available in a separate annual publications are now included in the ASNA.

1.41 In general terms, the information published in the ASNA and NIEP covers the economic transactions related to the economic functions of production, consumption and accumulation of wealth. The functions are recorded in a central set of accounts comprising a gross domestic product account, a national income account, a national capital account, a financial account and a balance sheet. Important economic variables such as gross domestic product, disposable income, final consumption expenditure, gross saving, net lending or borrowing and net worth are recorded in these accounts. Changes to the balance sheet values of financial assets and liabilities arising from events other than transactions (for example, write-offs and revaluations) are recorded in the ASNA. Supporting accounts in these publications provide further breakdowns (for example, by institutional sector and industry) of the variables recorded in the central accounts.

1.42 The information published in the Input-Output Tables and State Accounts can be described as further disaggregations of information included in the ASNA. For example, in the central Supply Use table, the economy's total supply of products is shown according to the industries that produced the products, and the use of products by each industry is recorded, as are the factor incomes generated by each industry. The information published in the State Accounts provides a summary record for each Australian State and Territory of the production account published in the ASNA.

1.43 Finance and Wealth includes disaggregations of information published in the ASNA and NIEP, but also includes disaggregations of balance sheet information for financial assets and liabilities. The financial accounts include flow of funds statistics, which provide sectoral capital accounts with the corresponding sectoral financial account. The financial accounts provide a breakdown (financial instrument cross-classified by counterparty sector) of transactions recorded in the financial account (counterparty sectors are the sectors with which the subject sector has undertaken the subject transactions). The financial accounts also record the value of financial assets and liabilities at the end of each quarter, broken down by instruments cross-classified by counterparty sector.

1.44 The satellite accounts for Tourism, Non-Profit Institutions and Information and Communication Technology present specific details on a particular topic (both in monetary and physical terms) in an account which is separate from, but linked to, the information published in the ASNA. Satellite accounts allow an expansion of the National Accounts for selected areas of interest while maintaining the concepts and structures of the core National Accounts. Implicitly data presented in satellite accounts are included in the National Accounts, but they can go further and include data that is not in the National Accounts at all.

1.45 In summary, the ASNA provides a record of Australia's economic wealth and the changes to that wealth brought about by economic activity. The Australian National Accounts statistics are also disaggregated to provide information about economic assets and activities for sectors, industries, and products, and about different types of assets, liabilities, transactions and other economic events. In terms of economic information, the scope of the statistics is therefore very wide, and the only economic activities omitted from that scope are those that fall outside the defined boundaries of production, consumption, accumulation and economic assets. Nevertheless, the ASNA does not necessarily provide all of the macroeconomic measures that analysts require, and statistical offices, including the ABS, are working to improve and extend the body of macroeconomic statistics.

General nature of ASNA methodology

1.46 The sources and methods used to compile National Accounts are typically many and varied, and the Australian situation is no exception. From the perspective of users of the ASNA, an understanding of the sources of information used and the methods applied to compile the National Accounts is useful because such matters can influence the quality, accuracy and reliability of the statistics. A detailed account of the sources and methods underlying the data compiled for key variables in the central transaction accounts and for specific sets of data, such as appear in the financial accounts and the balance sheets, are outlined in other sections. The next few paragraphs provide a broad description of the processes and infrastructure that underlie compilation of the ASNA.

1.47 Because of the wide range of information included in the ASNA, capture of the data by means of a single survey, or even a few surveys, would not be feasible. Since many parts of the accounts record transactions in which two parties are involved, there are at least two possible sources of information about such transactions, and compilers can economise by targeting the least costly sources of information without compromising the quality of the data significantly. Quality of the data source is of paramount importance. Furthermore, surveys are not the only sources of information, and advantage must be taken of administrative and other records that contain relevant information obtainable at less cost than surveys.

1.48 However, before using information from surveys or administrative records, National Accounts compilers must be sure that the information is consistent with national accounting standards and that there are no gaps or overlaps between the various sources. A high proportion of information used in compiling the Australian National Accounts comes from surveys that use the ABS register of businesses and other organisations (referred to as the 'business register') to provide the target population. The business register is a list of economic units that are defined according to national accounting standards. The units are also defined so as not to overlap, and every effort is made to include all economically significant units so that there are no gaps in the coverage of the relevant fields of economic activity. Although most of the ABS surveys that provide data for the ASNA are used primarily to compile other economic statistics, the survey questions are generally designed to comply with national accounting concepts so that the survey results are consistent with National Accounts statistics. Where administrative data are used, the National Accounts compiler has less control over the application of standards and the possible existence of gaps and overlaps. Some potential sources of this type may be rejected because they cannot be reconciled with survey results or deviate too much from National Accounts standards.

1.49 Once reliable and consistent sources of data have been established, the major task of the National Accounts compilers is to bring together the data in the national accounting framework. In some cases, there may be two sets of data relating to the same variables, in which case discrepancies must be investigated and a choice made as to which data are more reliable. Furthermore, the ASNA includes balances that are equal in concept but are derived from different data sources. For example, net lending or borrowing in the capital account is equal in concept to net change in financial position in the financial account but is derived entirely from non-financial transactions, whereas net change in financial position is derived entirely from financial transactions. Such balances provide a measure of the consistency of the two sets of data and can be used to monitor the accuracy and quality of the statistics. When differences are unavoidable or unresolved, rather than force a balance, compilers may record the differences in the accounts as 'statistical discrepancies' or 'net errors and omissions'.

1.50 Business and administrative records do not always provide information that reflects economic reality. For example, interest charges generally include a service charge as well as a return on capital invested. In such cases, the 2008 SNA prescribes imputation of the required information. In other cases, transaction flows have to be rerouted, as with employers' contributions to superannuation funds on behalf of their employees, which are paid to superannuation funds but are recorded in the ASNA as payable directly to employees as a component of employee remuneration. Therefore, National Accounts compilers must put in place systems to derive such imputed information. Thus, data obtained from surveys or administrative records may be adjusted or rearranged to meet the 2008 SNA requirements.

1.51 Two significant processes are applied by compilers to derive additional data of considerable interest: time series analysis and production of chain volume measures. Time series analysis includes seasonal adjustment and estimation of trend values. Seasonal adjustment involves estimation of seasonal factors in the data and adjustment of the data to remove the seasonal effect. Trend values are estimated by removing irregular movements from seasonally adjusted data. Chain volume estimation involves removing the effects of price changes from source data, which are recorded at current prices.

1.52 Once all adjustments and derivations have been made, compilers should have a complete dataset that can be checked for consistency with data for previous periods and data from other systems. Known as output editing, this form of checking aims to detect errors that may have slipped through at earlier stages of compilation, and which may require inquiry back to the supplier of the source data. Data may be queried because the resulting movement from the previous period (or the same period in the previous year) appears implausible or is inconsistent with the movement of other related variables. After all checks have been completed and errors or inconsistencies explained or removed, the statistics are cleared by a senior statistician for publication.

1.53 Australian National Accounts statistics include major economic indicators that are in strong demand and can influence financial markets. Therefore, care is taken to ensure that no user receives the statistics before the designated release time, with a small number of exceptions. These exceptions relate to designated officers in certain government departments, such as the Treasury and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, who are required to prepare briefing material on the statistics for their Ministers; they are subject to a strict embargo until the official release of the National Accounts.

1.54 Because Australian National Accounts statistics are often compiled from source data that are preliminary or incomplete, the statistics are often revised when final or more complete information comes to hand. Such revisions to the data are therefore relatively common. Furthermore, seasonally adjusted and trend data are subject to revision because the adjustment factors for seasonal and irregular influences change over time as more data are added to the time series. Similarly, chain volume measures are subject to revision whenever the reference period is changed and when a new base year is introduced.

Uses of Australian National Accounts statistics

1.55 The uses of the statistics included in the ASNA mainly arise from the role of the National Accounts as a framework for evaluating economic performance. However, given the wide range of information included in the ASNA, economic performance can be evaluated at a number of different levels, including the economy as a whole, the various sectors and subsectors of the economy, individual States and Territories, individual industries and individual products. Furthermore, information is available for different time frames, including quarterly data for measuring short-term changes in economic conditions and more detailed annual information for measuring longer-term changes. Seasonally adjusted and trend series facilitate analysis of short-term movements in quarterly data, and chain volume measures help to isolate volume movements in the economic indicators.

1.56 The estimates of national income, expenditure and product are well established as a framework for monitoring the current performance of the Australian economy, and are closely followed and analysed by government and private sector economists, the media, financial markets, credit rating agencies and others with an interest in current economic trends. General interest centres on trend and seasonally adjusted chain volume measures of key variables such as gross domestic product as an indicator of growth, measures of income such as compensation of employees (COE) and gross operating surplus (GOS) of corporations, the expenditure items of final consumption expenditure (government and households) and gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), the ratio of net household saving to net household disposable income, and production classified by industry groupings. Such information is used in short-term economic forecasting, in analyses underlying forecasts and economic policy settings in Commonwealth and State/Territory government budgets, in models of economic activity that simulate the effects of economic policy and behaviour, and in international comparisons of Australia's economic performance with the performance of other countries.

1.57 As well as Australia's National Accounts, the ABS produces annual accounts for each of Australia's States and Territories published in the State Accounts. These provide estimates of GSP and state final demand. An important use of the state accounts is to compare each State and Territory in terms of levels of economic activity and rates of economic growth.

1.58 The financial accounts data (published in Finance and Wealth) have more specialised uses, relating to financial markets and the financial sector. They are used by government and private sector economists as short-term indicators of the demand for credit, which reflects overall economic conditions and expectations. The sectoral and instrument breakdowns in the financial accounts enable detailed analysis of stocks and flows related to borrowing and lending. Depending on economic conditions, user interest may focus, for example, on the borrowing and debt of governments, or on the ratio of debt to equity financing of private corporations. The financial accounts provide an alternative view (to that shown in the real accounts) of national and sectoral saving, and indicate the composition of saving in terms of financial instruments. For example, these accounts can show trends in household saving toward superannuation and the extent of accumulation of household debt. Financial market analysts and participants use the financial accounts to assess growth in the markets for various forms of finance (e.g. deposits, loans, shares, debt securities) and sources of finance (e.g. banks, non-bank depository institutions, life offices and pension funds, non-residents) used by borrowers.

1.59 The national balance sheet data on the level and composition of Australia's assets and liabilities indicate the economic resources of, and claims on, the nation and each sector, and support assessments of the external debtor or creditor position of a country. The monetary estimates of natural resources contained in the balance sheet are underpinned by a dataset of physical estimates detailing levels of particular natural resources. Due to the experimental nature of the monetary estimates, it is considered that monetary estimates on natural resources should be considered in conjunction with the physical estimates, especially for mineral and energy resources. The estimates provide information for monitoring the availability and exploitation of these resources and for assisting in the formulation of environmental policies and resource pricing.

1.60 Sectoral balance sheets provide information necessary for analysing a number of topics. Examples include:

- the computation of widely used ratios, such as debt-to-equity, non-financial to financial assets, and debt-to-income; and

- the provision of additional information on the relationship between consumption and saving behaviour.

1.61 Companies can compare the return on their own assets with returns achieved nationwide. Prospective investors may examine the unit values and returns on; for example, the various mineral and energy resources to guide investments in particular industries.

1.62 The ASNA I-O tables provide a much more detailed disaggregation of gross domestic product than is available in the national income, expenditure and production GDP accounts. I-O tables are used to facilitate economic analysis in a number of ways, for example:

- they provide a means of undertaking comparative analysis of industries within an economy as well as across economies;

- they provide the basis for a detailed understanding of the linkages and dependencies that exist within an economy;

- given the set of assumptions implicit in the I-O framework, they provide a means of forecasting the economic effects of a change in demand on economic variables such as value added, prices and employment;

- they constitute a core component of many modern general equilibrium models which may be used for a number of purposes including forecasting; and

- they provide a framework whereby the confrontation of data from various sources can be undertaken, thereby providing a means of improving the accuracy of the National Accounts and economic statistics in general.

1.63 Satellite accounts are used to expand the analytical capacity of the National Accounts for selected areas of social concern in a flexible manner, without overburdening or disrupting the National Accounts. They involve the rearrangement of classifications used in the National Accounts and the possible introduction of complementary elements but do not change the underlying concepts of the National Accounts.

1.64 The National Accounts are used as a framework for other economic statistics. Given the comprehensive nature of the National Accounts coverage of economic activity, most economic statistics relate in some way to elements of the National Accounts. Conversely, National Accounts compilers draw upon a wide range of economic statistics to provide information for inclusion in the National Accounts. For these reasons, national statistical offices usually design economic statistics systems that are based on the concepts employed in the National Accounts. Such a strategy ensures that users of economic statistics can relate the statistics to the National Accounts, and that National Accounts compilers have sources of information that are conceptually compatible with the National Accounts. As noted previously, such an integrated approach to the production of economic statistics is followed in the ABS. It is administered through use of a single business register as the source of survey populations for most ABS economic statistics, and the strict application of national accounting concepts in the design of the business register and the surveys, including the units model, data item definitions and classifications.

Chapter 2 Overview of the conceptual framework

Introduction

2.1 The conceptual framework of the ASNA is based on the standards set out in 2008 SNA. The ASNA does not include all the elements of the 2008 SNA framework, although Australia's implementation is extensive. Some minor variations have been adopted in the ASNA to allow for specific Australian data supply conditions or user requirements; these are noted at appropriate points throughout this manual.

2.2 The ASNA records key elements of the Australian economy: production, income, consumption (intermediate and final), accumulation of assets and liabilities, and wealth. These elements comprise economic flows and stocks that are grouped and recorded, according to specified accounting rules, in a set of accounts for the economy as a whole and for various sectors and subsectors. The sectors and subsectors comprise groups of institutional units with the same economic role. Statistics are also produced for industries, which comprise groups of producing units with common outputs. At a more detailed level, I-O statistics are produced that record the supply and use of different types of goods and services, or products, by the various industries. Many of the statistics in the ASNA are compiled as current price and chain volume measures by application of 2008 SNA recommendations for price and volume measures.

The conceptual elements of ASNA

Institutional units and sectors

2.3 In 2008 SNA, the basic unit for which economic activity is recorded is the institutional unit. An institutional unit is an economic entity that is capable, in its’ own right, of owning assets, incurring liabilities and engaging in economic activities and transactions with other entities. In the Australian system, the legal entity unit is closest to the 2008 SNA concept of the institutional unit. However, in the ASNA, the unit used is the enterprise, which can be a single legal entity or a group of related legal entities that belong to the same institutional subsector. Four main types of institutional units are recognised in 2008 SNA and the ASNA: households, non-profit institutions, government units and corporations (including quasi-corporations).

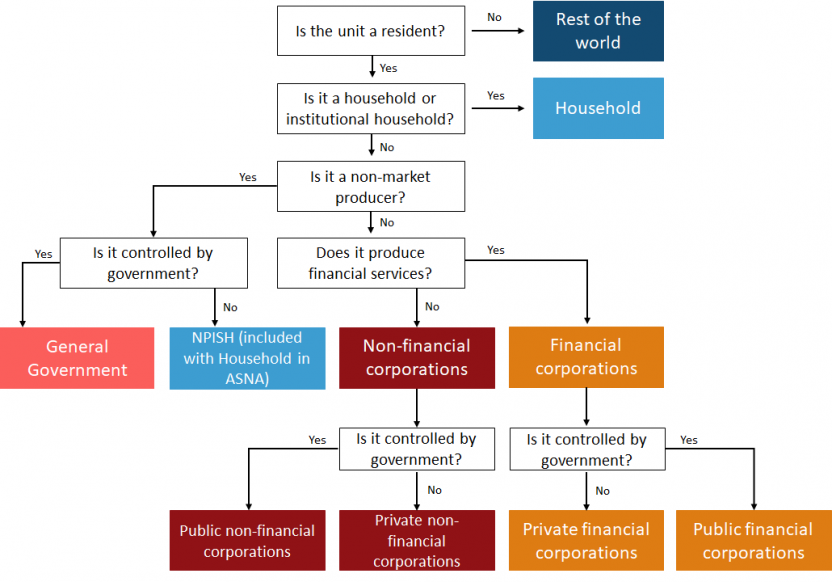

2.4 Institutional units are grouped into institutional sectors according to their characteristics and institutional role. All households are allocated to the household sector. Corporations and quasi-corporations are allocated to the non-financial corporations sector or the financial corporations sector according to whether their predominant function is production of goods and non-financial services, or production of financial services. Government units are all allocated to the general government sector. The allocation of non-profit institutions depends on the nature of their operations. Those mainly engaged in market production are allocated to the relevant corporate sector. Those mainly engaged in non-market production are allocated to the general government sector if they are controlled and mainly financed by government; otherwise, they are allocated to the non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH) sector. In the ASNA, the NPISH sector is included in the household sector.

2.5 The various domestic sectors and subsectors include only resident institutional units. The concept of residency used in the ASNA is the same as the concept used in balance of payments statistics, and is based on the requirement that an institutional unit must have a centre of predominant economic interest in Australia's economic territory to be an Australian resident unit.

2.6 Further detail on institutional units and sectors is outlined in Chapter 4.

Transactions and other flows

2.7 Economic flows reflect the creation, transformation, exchange, transfer or extinction of economic value and involve changes in the volume, composition or value of assets and liabilities. In the national accounts, economic flows are divided between transactions and other flows. Transactions generally involve interactions by mutual agreement between institutional units, but also include certain events that occur within institutional units, such as consumption of fixed capital and some types of production for the unit's own use. Other economic flows are changes in the value or volume of assets and liabilities that arise from events other than transactions, such as mineral discoveries, catastrophic losses, depletion, write-offs, and growth of natural assets.

2.8 The 2008 SNA groups elementary transactions and other flows into a relatively small number of types according to their nature. They are:

- Transactions in goods and services (products) describe the origin (domestic output or imports) and use (intermediate consumption, final consumption, capital formation or exports) of goods and services. By definition, goods and services in the SNA are always a result of production, either domestically or abroad, in the current period or in a previous one. The term products is therefore a synonym for goods and services.

- Distributive transactions consist of transactions by which the value added generated by production is distributed to labour, capital and government and transactions involving the redistribution of income and wealth (taxes on income and wealth and other transfers). The SNA draws a distinction between current and capital transfers, with the latter deemed to redistribute saving or wealth rather than income.

- Transactions in financial instruments (or financial transactions) refer to the net acquisition of financial assets or the net incurrence of liabilities for each type of financial instrument. Such changes often occur as counterparts of non-financial transactions. They also occur as transactions involving only financial instruments. Transactions in contingent assets and liabilities are not considered transactions in the SNA.

- Other accumulation entries cover transactions and other economic flows not previously taken into account that change the quantity or value of assets and liabilities. They include acquisitions less disposals of non-produced non-financial assets, other economic flows of non-produced assets, such as discovery or depletion of mineral and energy resources or transfers of other natural resources to economic activities, the effects of non-economic phenomena such as natural disasters and political events (wars for example) and finally, they include holding gains or losses, due to changes in prices, and some minor items.²⁵

Assets and liabilities

2.9 The 2008 SNA (with the ASNA being consistent) states that:

- Assets and liabilities are the components of the balance sheets of the total economy and institutional sectors. In contrast to the accounts that show economic flows, a balance sheet shows the stocks of assets and liabilities held at one point in time by each unit or sector or the economy as a whole. Balance sheets are normally constructed at the start and end of an accounting period, but they can in principle be constructed at any point in time. However, stocks result from the accumulation of prior transactions and other flows, and they are modified by future transactions and other flows. Thus, stocks and flows are closely related.

- The coverage of assets is limited to those assets which are subject to ownership rights and from which economic benefits may be derived by their owners by holding them or using them in an economic activity as defined in the SNA. Consumer durables, human capital and those natural resources that are not capable of bringing economic benefits to their owners are outside the scope of assets in the SNA.

- The classification of assets distinguishes, at the first level, financial and non-financial (produced and non-produced) assets. Most non-financial assets generally serve two purposes. They are primarily objects, usable in economic activity and, at the same time, serve as stores of value. Financial assets are necessarily and primarily stores of value, although they may also fulfil other functions.²⁶

Products and producing units

2.10 Goods and services, also called products, are the result of production. They are exchanged and used for various purposes: as inputs in the production of other goods and services, as final consumption or for investment. Institutional units may produce a variety of products and therefore can be too heterogeneous in terms of their productive activity to provide useful information about industries. Hence 2008 SNA specifies the use of narrower units than institutional units for the purpose of providing statistics about production classified by industry.

2.11 The producing unit recommended in 2008 SNA is the kind-of-activity unit, which is a part of an institutional unit that engages in one productive activity. However, 2008 SNA also suggests that an alternative unit can be used, namely the establishment, which covers all productive activity at a single location.

2.12 In the ASNA, the producing unit is the type of activity unit (TAU), which is the largest unit within a business for which relevant accounts are kept, having regard for industry homogeneity. However, ASNA does not recognise an establishment unit as outlined in 2008 SNA.

2.13 In the ASNA, each TAU is classified to an industry that is defined in the ANZSIC06, which is based on the principles and classification structure set out in the United Nations' International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities (ISIC), Rev.4. ISIC is the industry classification that the 2008 SNA recommends for use in national accounts.

2.14 Further detail on products and producing units is outlined in Chapter 5.

Relationship with other conceptual frameworks

2.15 The national accounts are important for providing a framework for economic statistics. The accounts provide a conceptual framework for ensuring the consistency of the definitions and classifications used in different, but related, fields of statistics. It also acts as an accounting framework to ensure the numerical consistency of data drawn from different sources. Consistency between different statistical systems enhances the analytical usefulness of all the statistics involved. Therefore, the harmonisation of 2008 SNA and related statistical systems is a key feature of the system.

2.16 ASNA is also harmonised with other statistical systems: the balance of payments, government finance statistics, and monetary and financial statistics. Australia's balance of payments was updated and aligns with BPM6, which was updated simultaneously with the 2008 SNA. Australia's government finance statistics, which feed into the national accounts, align with the International Monetary Fund's revised GFSM released in 2014.

Rules of accounting

2.17 Fundamental to the national accounts is the measurement of economic activity within the economy, i.e. the recording of the transfer of products from one unit to another. 2008 SNA states:

… a distinction is made between legal ownership and economic ownership. The criterion for recording the transfer of products from one unit to another in the SNA is that the economic ownership of the product changes from the first unit to the second. The legal owner is the unit entitled in law to the benefits embodied in the value of the product. A legal owner may, though, contract with another unit for the latter to accept the risks and rewards of using the product in production in return for an agreed amount that has a smaller element of risk in it. Such an example is when a bank legally owns a plane but allows an airline to use it in return for an agreed sum. It is the airline that then must take all the decisions about how often to fly the plane, to where and at what cost to the passengers. The airline is then said to be the economic owner of the plane even though the bank remains the legal owner. In the accounts, it is the airline and not the bank that is shown as purchasing the plane. At the same time, a loan, equal in value to payments due to the bank for the duration of the agreement between them is imputed as being made by the bank to the airline.²⁷

2.18 The 2008 SNA and ASNA accounting rules cover the valuation, time of recording and grouping by aggregation, netting and consolidation of individual stocks and flows.

2.19 All entries in the national accounts should be recorded at the market price current at the time of recording. The appropriate value for exchanges of goods and services is generally the transaction price. Where no transaction price is available, reference is made to the market value of similar goods and services. When no market prices of equivalent goods and services are available, the goods and services are valued at cost. By convention, all non-market goods and services produced by government units and non-profit institutions are valued at cost. Some goods are valued by writing down (depreciating) the initial acquisition costs. Where none of the foregoing methods is feasible, use can be made of the present value of expected future returns. However, this method is not generally recommended.

2.20 2008 SNA recommends that all economic flows be recorded in the national accounts on an accrual basis (i.e. when economic value is created, transformed, exchanged, transferred or extinguished). Accrual recording ensures that economic events are recorded consistently and without distortion arising from leads and lags in accompanying cash flows. In general, use of accrual recording means that:

- flows involving change of ownership are recorded when ownership changes;

- services are recorded when provided;

- distributive transactions, which are those associated with the distribution of income to owners of the factors of production, are recorded as amounts payable accumulate;

- interest is recorded as it accumulates rather than when it falls due for payment;

- output is recorded as production takes place; and

- intermediate consumption is recorded when goods and services are used

2.21 For the most part a strict accrual basis of recording is applied in the ASNA, although special procedures are sometimes required to estimate certain flows on an accrual basis.

2.22 In the national accounts, data are recorded in aggregates (i.e. the sums of the values of stocks and flows of a given type such as total output) and balancing items (i.e. the differences between aggregates on each side of an account or between other balancing items such as saving). A degree of netting is employed in the national accounts in as much as transactions with opposite sign are often combined (e.g. acquisitions and disposals of financial assets are recorded as 'net acquisitions'). Consolidation refers to the elimination of transactions between units in the same sector or subsector from aggregates. In the ASNA, consolidation is generally confined to transactions within establishments, to transfers between institutional units within the general government and household sectors, and to transactions in used fixed assets within sectors. In contrast to 2008 SNA, property income flows within institutional sectors and sectoral (or subsectoral) transactions in financial instruments are consolidated in ASNA. Transactions between establishments of the same enterprise are generally not consolidated, however transactions in financial instruments and related income flows are fully consolidated.

2.23 National accounting is based on the principle of double entry as in business accounting. Each transaction must be recorded twice, once as a resource (i.e. income) and once as a use (i.e. expense). The total of transactions recorded as resources and as uses must be equal, thus permitting a check on the consistency of the accounts. Economic flows that are not transactions have their counterpart directly as changes in net worth. The recording of the consequences of an action as it affects all units and all sectors is based on a principle of quadruple entry accounting, because most transactions involve two institutional units. Correctly recording the four flows involved ensures full consistency in the accounts.

2.24 Further detail on accounting rules is available from Chapter 3.

Endnotes

The Accounts

The full sequence of accounts

2.25 2008 SNA divides the accounts into two main classes: the integrated economic accounts and the other parts of the accounting structure. The integrated economic accounts use the institutional units and sectors, transactions, and assets and liabilities together with the rest of the world to form the accounts. These are the accounts presented in ASNA, but not in the same format. The other parts of the accounting structure bring in the conceptual elements of production units, products, purposes, employment and population to assist in the production of the integrated economic accounts (e.g. supply-use tables) or to present the data in different ways.

2.26 The integrated economic accounts are grouped into three categories:

- Current accounts - present production, and the generation, distribution and use of income;

- Accumulation accounts - present changes in assets and liabilities and changes in net worth (the difference between assets and liabilities for a given institutional unit or group of units); and

- Balance sheets - present stocks of assets and liabilities and net worth. Opening and closing balance sheets are included with the full sequence of accounts.

2.27 The main accounts in the ASNA are as follows:

- gross domestic product (GDP) accounts - record the value of production (i.e. production of GDP), the income from production (i.e. income from GDP) and the final expenditures on goods and services produced and net international trade in goods and services (i.e. expenditure on GDP);

- income accounts - show primary and secondary income transactions, final consumption expenditures and consumption of fixed capital;

- capital accounts - record the net accumulation of non-financial assets through transactions, and the financing of the accumulation by way of saving and capital transfers;

- financial accounts - show the net acquisition of financial assets and the net incurrence of liabilities; and

- balance sheets - record the stock of financial and non-financial assets, and financial liabilities at a particular point in time.

2.28 The ASNA accounts are based on the system of accounts outlined in 2008 SNA. Each of the accounts is produced for the economy as a whole and the set of accounts together constitute the consolidated summary accounts. The ABS produces annual income and capital accounts by institutional sector based on 2008 SNA. The quarterly sectoral accounts depict national accounts using the same concepts and definitions as the annual sector accounts. These accounts are compiled for each of the following institutional sectors and subsectors: non-financial corporations (private and public), financial corporations, general government (national and state and local), and households (including NPISH).

2.29 The national accounts also include supplementary tables which provide more detailed presentations of the individual sector accounts. Although production accounts could be constructed for the four individual institutional sectors, major interest centres instead around production on an industry basis. This cuts across the institutional sectors used in the income and capital accounts since the production units are classified by industry without regard to institutional sector.

2.30 Another account that is integral to the national accounts is the external account. This account records the transactions and financial positions of the nation with the rest of the world, from the point of view of the rest of the world. In one sense, the external account is simply another sectoral account. Because of the important role of the rest of the world sector, the account is a major focus of attention for economic analysts and international organisations.

GDP accounts

2.31 The measure of production for the economy as a whole is gross domestic product (GDP). GDP is the sum, for a particular period, of the gross value added of all resident producers (where gross value added is equal to output less intermediate consumption) and net taxes on products. This is referred to as GDP measured by the production approach (GDP(P)). GDP can also be derived as the sum of factor incomes (i.e. compensation of employees, gross operating surplus and gross mixed income) and net taxes on production and imports, or as the sum of all final expenditures by residents (final consumption expenditure and GFCF), changes in inventories and exports less imports of goods and services. These are referred to as GDP measured by the income approach (GDP(I)) and GDP measured by the expenditure approach (GDP(E)), respectively. All three approaches are presented in the ASNA publications. In Australia, the combined presentation of the three approaches is referred to as the GDP accounts. These reflect the 2008 SNA production account.

2.32 Although conceptually each measure should result in the same estimate of GDP, different estimates of GDP are obtained when the three measures are compiled independently using different data sources. However, integration of the annual Australian national accounts estimates with annual balanced supply-use tables ensures that the same estimate of GDP is obtained for all three approaches for years in which these tables are available. The supply-use tables have been compiled from 1994-95 up to the year preceding the latest completed financial year, except in the June quarter where it is the latest two years.

2.33 Prior to 1994-95, the estimates using each approach are based on independent sources and there are usually differences between the GDP I, E and P estimates. Nevertheless, for these periods, a single estimate of GDP has been compiled by taking a simple average of the I, E and P estimates.

2.34 As a result of the above methods:

- there are no statistical discrepancies in either current price or chain volume terms for annual estimates from 1994-95 up to the year prior to the latest year (and the latest two years in the June quarter); and

- statistical discrepancies exist in both current price and chain volume terms between estimates obtained from the GDP I, E and P approaches and the single estimate of GDP for years prior to 1994-95, for the latest year (and the latest two years in the June quarter), and for quarterly estimates. These discrepancies are shown in the relevant tables.

2.35 There is no institutional sector dimension to any of the GDP accounts, although the GDP(I) measure could be classified this way. GDP measured by the production approach (i.e. sum of value added) is presented by industry only. The valuation of GDP in ASNA is at purchasers' prices, so net taxes on products are added to total gross value added to obtain GDP(P).

Income account

2.36 2008 SNA splits the income account into several accounts, distinguishing between the distribution, redistribution and use of income. The distribution of income is decomposed into three main steps: primary distribution (i.e. primary income), secondary distribution (i.e. secondary income) and redistribution in kind (i.e. social transfers in kind). The balancing items at the various stages are meaningful concepts of income provided all kinds of distributive current transactions are included.

2.37 The ASNA includes all such transactions. Each stage is presented in the income account with the balancing items being gross income and gross disposable income for all sectors, and adjusted disposable income for the general government and household sectors. Australia's presentation of the income account differs from 2008 SNA in that transactions regarding the distribution and redistribution of income are presented in one table.