Data linkage and integration to improve the evidence base for public policy: lessons from Australia

Health Economics Research Centre, Nuffield Department of Population Health

University of Oxford, United Kingdom

Introduction

Thank you, Philip, for the invitation to present today.

The digital revolution, to which we have all borne witness, has as a by-product generated many large administrative datasets, from both the public and private sectors. These administrative datasets offer the prospect of being linked together, or integrated, to enable analysis of public policy problems for which a single dataset is insufficient.

In my talk today, I will do two things.

First, provide a history of the development of the two largest and most extensive integrated data assets in Australia and second, give examples of public policy questions now being tackled using these integrated data assets.

BLADE and PLIDA

The first of the integrated data assets I will be talking about is focussed on business and the second on people. They are called BLADE and PLIDA, which stand for Business Longitudinal Analysis Data Environment and Person-Level Integrated Data Asset. Both assets are longitudinal: the core datasets in BLADE span the years 2001 to 2024, while those in PLIDA span the years 2006 to 2024. Both assets are hosted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.[2]

While these two data assets are large and extensive, they are not the only prominent Australian integrated data assets.[3]

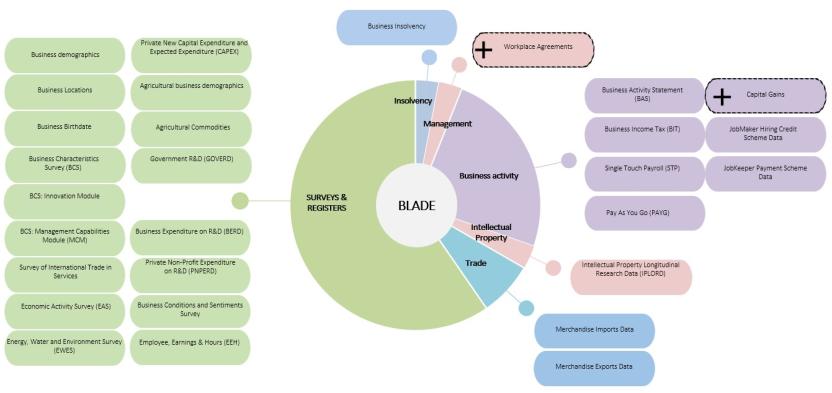

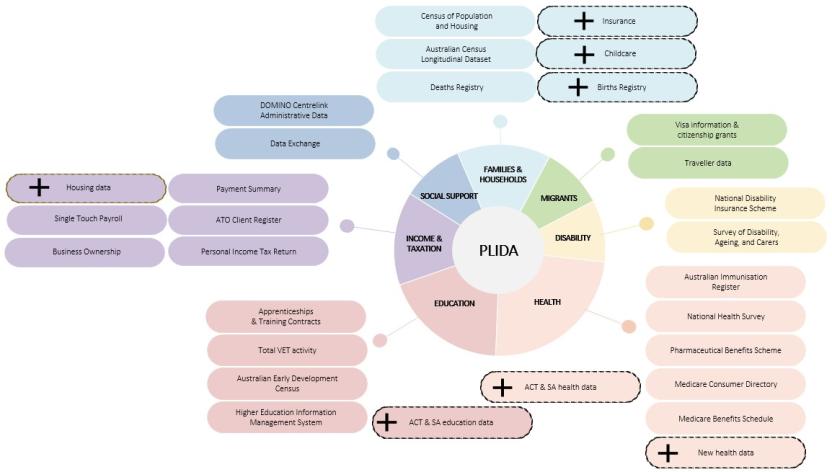

Figures 1 and 2 below show the datasets currently included in BLADE and PLIDA. BLADE currently integrates 29 datasets including surveys on a wide range of business characteristics, data on business income and tax, on exports and imports, insolvency, and employment conditions. PLIDA currently integrates 30 datasets including the Census, tax return data, data on social security recipients, migrants, and on health, education, and disability.

New datasets are added when there is a new policy need and/or the opportunity arises. Those datasets marked with a ‘+ sign’ in the figures are currently being added to the integrated data assets.

These integrated data assets therefore provide analysts with powerful tools to shed light on public policy problems across multiple dimensions.

Figure 1: Business Longitudinal Analysis Data Environment (BLADE) Datasets

Image

Description

This figure outlines all the datasets included in the Business Longitudinal Analysis Data Environment (BLADE). BLADE is an economic data tool combining tax, trade and intellectual property data with information from ABS surveys to provide a better understanding of the Australian economy and businesses performance over time.

Figure 2: Person-Level Integrated Data Asset (PLIDA) Datasets

Image

Description

This figure outlines the all the datasets included in the Person-Level Integrated Data Asset (PLIDA). PLIDA is a secure data asset combining information on health, education, government payments, income and taxation, employment, and population demographics (including the Census) over time. It provides whole-of-life insights about various population groups in Australia, such as the interactions between their characteristics, use of services like healthcare and education, and outcomes like improved health and employment.

History

Support for comprehensive integrated data assets built gradually in Australia. Developments at the time in other countries, particularly New Zealand, drew attention to what was being done elsewhere, and what might be possible.

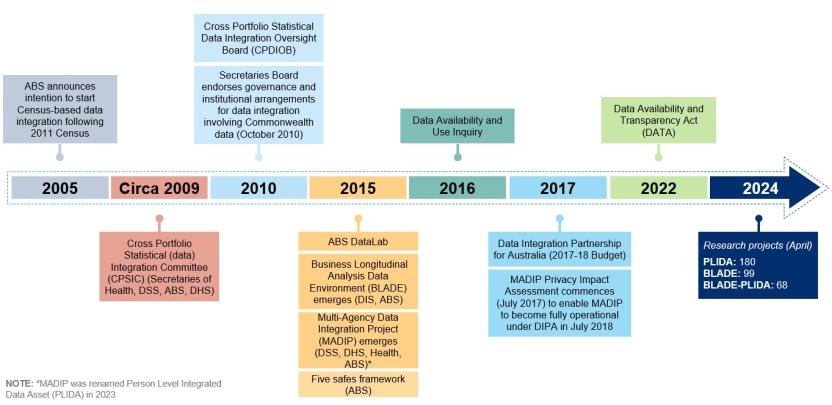

Figure 3 below shows a timeline of the major events that led to the development and growth of BLADE and PLIDA in Australia.

Figure 3: Timeline for Data Integration

Image

Description

This figure shows a timeline of the major events that led to the development and growth of BLADE and PLIDA in Australia.

As the figure above shows, there were Boards and Committees set up around 2010 that provided support for data integration at the most senior levels of the Australian Public Service.

In the subsequent few years, progress was gradual. There was some criticism at the time that the ABS had overly restrictive rules that were impeding the development of integrated data assets and access to researchers.[4] There was also concern in the broader public service about the risks associated with data sharing.

The critical developments that led to the first versions of both BLADE and PLIDA occurred in 2015.

The development of BLADE was largely the initiative of two public servants, Dr Luke Hendrickson, who worked for Mark Cully, Chief Economist at the Department of Industry and Science, and Diane Braskic, who headed up the industry statistics team at the ABS. They convinced their superiors of the value of their idea, and Mark convinced his department to provide a one-off $AUD 5 million in funding to launch what subsequently became known as BLADE.

Also in 2015, a group of public servants from four key Federal government agencies agreed to launch a project to develop a people-centred integrated data asset.[5]

It began small, linking together Social Security and Related Information, Personal Income Tax, Medicare Benefits Schedule, Medicare Enrolments Database and the (most recent) 2011 Census of Population and Housing.

This new integrated data asset was carefully designed with strong protections to ensure the privacy of individuals was maintained. Notwithstanding the strength of these protections, the initial name – Multi-Agency Data Integration Project (MADIP) – highlighted the partnership aspect of the project without being explicit about the key idea behind the asset, which was to link unit records about individuals across a range of subject-matter areas.[6]

Six subsequent developments were key to getting us to where we are today.

First, the introduction of a trusted access model for integrated data assets, the ‘Five Safes’ framework. The framework’s developer, Professor Felix Richie, from University of the West of England, Bristol, was invited to Canberra in November 2015 to take part in a workshop hosted by the Australian Academy of Social Sciences, ABS and Department of Social Services, to broaden understanding of the Five Safes as it was being adopted by the ABS.[7]

Second, the development and refinement of the ABS DataLab, the secure environment in which to conduct analysis of ABS integrated data assets. DataLab was launched in 2015 as a secure facility but, to access it, analysts had to travel to an ABS office in one of Australia’s capital cities. It transitioned to a virtual secure offering from 2016, access for academic research was enabled from 2019, and the technology was upgraded to use cloud-based infrastructure from 2020. Together, these enhancements facilitated enormous growth in the use of integrated data assets via the DataLab, both by universities and government agencies. Most recently, it has been made available to select overseas researchers working on Australian public policy projects who access the DataLab from outside Australia in a pilot.[8]

Third, the gradual acceptance across the senior echelons of the Australian Public Service that datasets should be integrated where feasible, because of the powerful contribution they could make to public policy formulation and evaluation. Some people readily accepted this argument while, in other cases, acceptance occurred as key people retired and were replaced by others more favourably disposed to support the integration of datasets for which they were custodians.[9]

Fourth, direct government support via the Data Integration Partnership for Australia, a three-year (July 2017 to June 2020) $AUD131 million investment to enhance public sector data assets, including substantial investments in BLADE and MADIP.[10]

Fifth, the COVID-19 pandemic, which generated urgent new public policy questions which could be answered only using integrated data. This demonstrated to government and the wider public service the capacity of integrated data assets to shine light on important public policy questions. It also provided the impetus to streamline processes in data integration and access, leading to much more frequent updating of the underlying datasets.[11]

And sixth, over time, the ABS data integration team developed deep expertise in data linkage, maintaining data privacy, negotiating for new datasets, and providing support for the expanding number of researchers seeking access to these data assets.

Improving the Evidence Base for Public Policy

As of April 2024, there were nearly 350 active research projects in the DataLab accessing ABS-hosted integrated data assets. Of these, about one third use BLADE, about a half use PLIDA and the remainder use a combination of both. About half are university projects, one third are government projects, Federal and State, with the remainder internal ABS projects and projects undertaken by Australian think tanks like the Grattan Institute and e61.

The 1,700 analysts working on these projects do so after receiving training on how to use the DataLab and on the importance of maintaining the privacy of the underlying data.[12]

Let me turn now to describe some of the public policy issues being tackled using Australian integrated data assets.

In the early phase of the pandemic, the ABS developed the Labour Market Tracker for the Federal Treasury Department. This is an integrated dataset using elements of both BLADE and PLIDA to link employees to their employers and to understand flows between employment and the range of support payments put in place to soften the economic impact of the pandemic. Among other things, it enabled Treasury to have a detailed understanding of labour market outcomes when it provided advice on the appropriate timing of the winding down of JobKeeper (the main support payment for laid-off workers).[13]

Treasury is now extending the Labour Market Tracker, using worker flows to develop a mergers database to give a much more complete picture of Australian mergers and acquisitions than is available to the Australian Consumer and Competition Commission, the regulator responsible for assessing mergers in Australia.

The aim is to link with other administrative datasets to enable examination of the impact of mergers on wages, productivity, market share and other economic outcomes.[14]

To give a quite different example, analysts are using both BLADE and PLIDA to track the contribution over time of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses to employment and the wider Australian economy. The longitudinal nature of the data enables analysts to explore growth in the economic contribution of indigenous businesses over time and examine ways in which they differ from non-indigenous businesses.[15]

In a third example, the Department of Health used the link between PLIDA (in particular, the Census) and the Australian Immunisation Register to identify groups with low-vaccine uptake who spoke languages other than English. Table 1 shows some of the results as of mid 2022. The level of detail shown in the table enabled communication campaigns, digital translations, and community outreach activities to be developed in close to real time to lift vaccine rates for those groups with low uptake identified by the analysis.

Table 1: COVID-19 vaccination uptake by language group and country of birth, as at 17 July, 2022

Image

Description

This table outline COVID-19 vaccination uptake by language group and country of birth, as at 17 July, 2022.

The link of these data with up-to-date Single Touch Payroll data (which links workers with their employers) meant the Department of Health could also examine vaccination rates for those working with vulnerable people such as aged care residents.

The link between PLIDA and the Australian Immunisation Register was also used by an academic study which followed 3.8 million Australians aged 65 and over in 2022 to examine the relationship between mortality for this older age group and vaccination status.

The study demonstrated that in early 2022, a 65+ year old person having had three COVID-19 vaccinations – with the third dose administered within the previous three months – had a COVID-19 mortality reduced by 93 per cent relative to a comparable unvaccinated person.

The study also demonstrated how vaccine effectiveness wanes over time. It showed that people who received their most recent booster within the previous three months had a much larger reduction in mortality (by around 20 percentage points) than people whose latest booster had been more than six months ago. Being vaccinated reduced mortality significantly relative to the unvaccinated but the level of protection was noticeably higher for those with a recent booster.

By looking at all-cause mortality, the study also definitively disproved any positive association between COVID-19 vaccinations and other causes of death.

Conclusion

Let me summarise what I think are the ingredients that go into building and maintaining high-quality integrated data assets for public policy purposes.

I have eight.

First, you need some individual public servants – who may be quite junior – to work up proposals for data integration projects. To begin with, this seems like a step into the unknown and comes with obvious risks – it might not be widely supported, and it might fail.

Second, and relatedly, as well as support from government, support from key senior people in the public service is needed. This support needs to be expressed publicly and it needs to be not only in principle but also in practice when specific data sharing proposals come forward.

Third, interested observers in the wider community need to recognise the benefits of what can be achieved by integrating data assets and that the benefits outweigh the risks of integrating datasets across a range of subject-matter areas – that is, data integration must build and maintain its social licence.

Fourth, it makes sense to start small. Start by integrating a limited number of data assets and demonstrating the value they can generate by way of public policy insights. Then build from there.

Fifth, the project needs to be a partnership. For large integrated data assets, data custodians come from many different government departments and agencies (and potentially from sectors beyond government as well), and these data custodians need to share an interest in the project succeeding rather than feeling it has been foisted upon them against their better judgement.

Sixth, you need a sustainable source of funding. Integrated data assets provide much value. But maintaining them securely with appropriate privacy protections, which in our case involves hosting them in the cloud, and updating them frequently, is expensive.

Seventh, you need perseverance. Adding new datasets to an integrated data asset brings the benefit of widening the range of public policy questions that can be tackled. However, it also brings risks, including that analysts will derive insights that are unwelcome for the government of the day. That potential outcome can generate resistance for the data integration in the first place. Perseverance is needed to overcome resistance and maintain support for the wider benefits of data integration.

Eighth, you need a pool of skilled analysts who can derive useful public policy insights from complex linked data. As this pool grows, integrated data becomes increasingly acknowledged as an essential tool for informed policy making.

In conclusion, Australia’s recent experience building powerful integrated data assets has been a positive one. Important public policy questions and careful evaluations of public policy can often be tackled using integrated data assets. While there will always be a role for randomised control trials, many public policy questions can be studied and evaluated using these new data assets.

Thank you.

Footnotes

1. Diane Braskic, Mark Cully, Teresa Dickinson, Phillip Gould, Pete Harper, Luke Hendrickson, Bindi Kindermann, Gemma Van Halderen, Marcel van Kints and Jenny Wilkinson provided extremely helpful comments on an earlier draft.

2. Datasets are ‘integrated’ when they are linked together so that analysts can study several aspects of individuals’ (or individual businesses’) behaviour together. The unit records are linked together in such a way that records from different datasets (for example, health and tax records) are identified as being for the same person (or same business). This is done via a spine that is common across the linked datasets (see https://www.abs.gov.au/about/data-services/data-integration/person-linkage-spine for further information). The individual records are de-identified so that privacy is preserved, and the identity of individuals (or individual businesses) is not revealed. It is incumbent on the hosts of these data assets, in this case the ABS, to ensure they are secure, with well-developed protocols to ensure the private information of individuals and businesses is protected and is not compromised.

3. Others hosted in Federal public service agencies are the National Disability Data Asset, being developed by the ABS, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) and the Department of Social Services; Alife, hosted by the Australian Taxation Office; the National Integrated Health Services Information, hosted by the AIHW, and other integrated data assets hosted by the ABS including the Australian Census Longitudinal Dataset (see https://www.abs.gov.au/about/data-services/data-integration). Other integrated data assets are hosted by State governments and universities.

4. For example, in published remarks at a March 2015 conference, Mark Cully, Chief Economist at the Department of Industry and Science, expressed his view that ‘… business statistics have long been the poor cousin of social statistics in Australia. This has not been helped by an official mindset that tends to see business statistics as inputs to compiling the national accounts, rather than as data of analytical interest in their own right. Very tight access restrictions for outside researchers to firm-level data held by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has also been a factor.’ https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/confs/2015/andrews-criscuolo-gal-menon-disc.html

5. While others were involved, the key people who initiated the project were Peter Harper and Gemma Van Halderen from the ABS, Paul Madden from Health, Barry Sandison from Human Services and Sean Innis from Family and Community Services, Housing and Indigenous Affairs (subsequently Social Services).

6. The name was changed in 2023 to Person-Level Integrated Data Asset (PLIDA) – which describes the nature of the data asset rather than the collaboration that created it.

7. For more, see https://www.abs.gov.au/about/data-services/data-confidentiality-guide/five-safes-framework.

8. Making Australian data available to international researchers should raise interest in Australian policy issues that can be tackled using these data and contribute to improving analysis of these policy problems. Over the past couple of years, the ABS has worked closely with the OECD and the University of Chicago’s Professor Greg Kaplan to pilot international researcher access to BLADE and PLIDA. Before this pilot, only researchers located in Australia could access BLADE and PLIDA. Over 2024, the ABS, in consultation with other Australian government agencies, will assess the risks and benefits of making BLADE and PLIDA available more broadly to international researchers.

9. This recalls Max Planck’s aphorism that science progresses one funeral at a time. “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” Max Planck, Scientific autobiography, 1950.

10. DIPA was a collaboration of over 20 Federal agencies, and improved technical data infrastructure and data integration capabilities across the APS.

11. The earlier standard was to update the underlying data in BLADE and MADIP once a year. With the arrival of the pandemic, data from the Australian Immunisation Register, which records vaccinations for every Australian as they occur, was linked to MADIP each week, and provisional death registrations data was linked and updated monthly.

12. Everyone using the DataLab first signs an undertaking that they will not attempt to re-identify any individual or business in the unit records they access.

13. See https://treasury.gov.au/publication/p2021-211978 and https://www.abs.gov.au/system/files/documents/dd267c4bbee2318ccdaa8a6cd5e54974/Cully%2C%20Whalan%20-%20Looking%20under%20the%20lamppost%2C%20new%20data%20for%20unseen%20challenges.pdf

14. See https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-01/Competition-Review-Mergers-FA.pdf